Revolution — Part 2

1848 Revolution in Paris By Henri Félix Emmanuel Philippoteaux, Public Domain

While we previously discussed the French Revolution of 1789, we will now look to better understand the year 1848 — a world caught up in the fire of revolution. This fire was widespread around the globe with consequences far and wide. And out of this overturned world, came the rise of a prophet.

In 1848, revolution swept across Europe and the world. The “February Revolution” in Paris lit the flame as the current world order was crumbling. In the days leading up to the overthrow of the French King Louis-Phillippe, the historian Alexis de Tocqueville commented on the state of Paris:

One thing was.. really ominous and terrible; and that was the appearance of Paris on my return. I found in the capital a hundred thousand armed workmen formed into regiments, out of work, dying of hunger, but with their minds crammed with vain theories and visionary hopes. I saw society cut into two: those who possessed nothing, united in a common greed; those who possessed something, united in a common terror. There were no bonds, no sympathy between these two great sections; everywhere the idea of an inevitable and immediate struggle seemed at hand. Already the bourgeois and the people had come to blows, with varying fortunes… not a day passed but the owners of property were attacked or menaced in either their capital or income…

With the overthrow of the monarch, came the beginnings of the Second French Empire, and the dictatorship of Napoleon III. Kindled in part by the utopian socialist philosophies espoused by Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels, and Charles Fourier, this revolutionary spirit soon spread from Paris like wildfire. Uprisings soon began throughout the Hapsburg empire. These forced the resignation of Prince Von Metternich and the beginnings of the empire’s decay. Throughout Berlin and other German cities, barricades were put up as civilians and soldiers clashed.

Nicholas 1’s Russia soon found itself caught up in this same spirit of revolution. Small Revolutionary groups emerged in many of the cities around the country, as radicals hoped to cause societal upheaval and change. Among the more influential of these groups was the Petrashevsky Circle in St. Petersburg. Upholding the views and philosophies of Charles Fourier, the group sought to bring utopian socialism to Russia and upend the tsarist regime. Among the key members of the Petrashevsky Circle was Fyodor Dostoevsky.

The canals of St. Petersburg, photo by Puja Lin on Unsplash

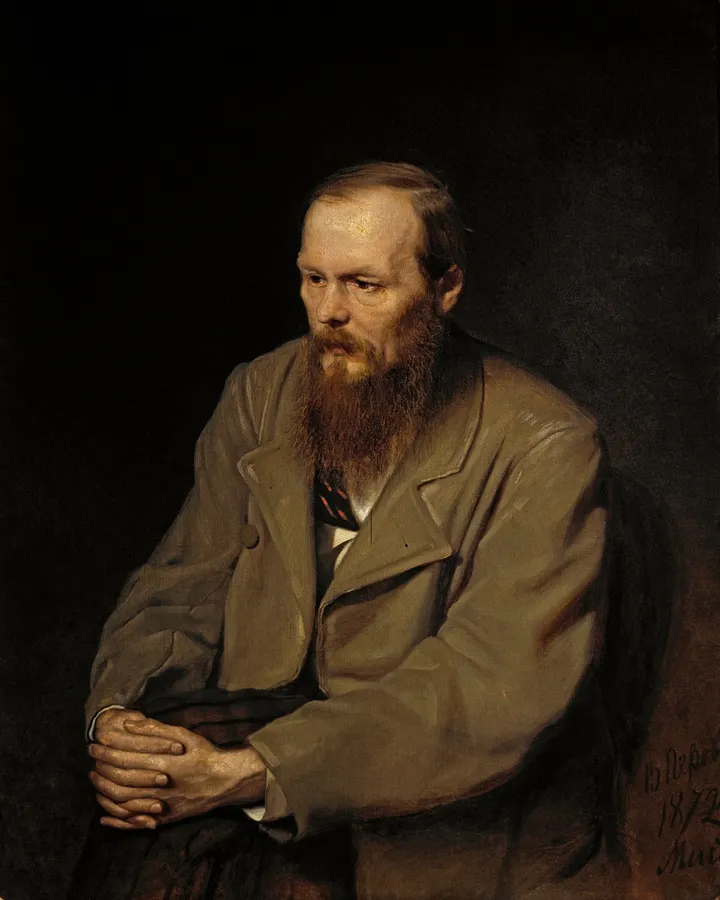

Afew years prior to the tumultuous year of 1848, Fyodor Dostoevsky had burst onto the literary scene in Russia with his first novella Poor Folk. Met with immediate literary success, this short work portrayed life for the average Russian citizen in the capital city of St. Petersburg. The book immediately propelled the young 25 year old Dostoevsky, into St. Petersburg’s famed literary clique. Dostoevsky was now part of the “club” that had once boasted the likes of world famous authors Alexander Pushkin and Nikolai Gogol.

Over the next few years Dostoevsky continued to write, producing several fascinating novels — The Double and White Nights. Unfortunately, these works did not have the economic success that Poor Folk received. Because of this, Dostoevsky soon found himself in extreme financial struggles. These struggles, in addition to his extremely liberal views, led to Dostoevsky fitting in with many of the radicals of St. Petersburg. Before long, the young Dostoevsky found himself as one of the leaders of the Petrashevsky Circle.

Drawing by B. Pokrovsky

In response to the spirit of revolution spreading across Europe and the world, Tsar Nicholas 1 began to crack down on the radical groups around Russia. To squelch any chance of revolt in his country, the Tsar began imprisoning the members of the Petrashevsky Circle. Dostoevsky was among them. The prisoners were held in the Peter and Paul Fortress for several months. Then, in one of the defining moments of Dostoyevsky's life, all the members of the Petrashevsky were led to one of the city’s squares and prepared to be executed. Dostoevsky recalls what happens in a letter to his brother:

Today, the twenty-second of December, we were taken to the Semyonov drill ground. There, the sentence of death was read to all of us, we were told to kiss the cross, and our swords were broken over our heads… Then (we) were tied to the pillar for execution. I was the sixth… and no more than a minute was left me to live.

Finally the retreat was sounded and those tied to the pillar were led back, and it was announced to us that His Imperial Majesty granted us our lives. Then followed the present sentences… I am sentenced to four years’ hard labor in the fortress (of Orenburg, I believe), and after that to serve as a private.

With a renewed lease on life, Dostoevsky and the other revolutionaries spent the next four years in the Katorga prison camp in Omsk, Siberia. During this time in the labor camp, he was only allowed to read the New Testament. In these unimaginable conditions that Dostoevsky faced, he rediscovered the Christian faith. Until 1859, Dostoevsky spent his time in labor camps and in military service in Siberia.

Portrait of Fyodor Dostoevsky (1872), painted by Vasily Perov

In 1863, Nikolai Chernyshevsky wrote the novel What is to be Done?, a utopian tract espousing a godless socialist society. The novel had an enormous effect throughout Russia, and later greatly influenced many revolutionaries. Among those heavily influenced by Chernyshevsky’s book was Vladimir Lenin, who later became enamored by the novel while a student and wrote a book with the same title. Dostoevsky was greatly opposed to Chernyshevsky’s progressivist novel, and in response, wrote Notes From the Underground. Through Notes From the Underground, Dostoevsky was again propelled onto the Russian literary scene. In the book, Dostoevsky attempts to show his readers the logical conclusion of a godless worldview that believes it can solve the world’s many problems through enlightenment. A world as espoused by Chernyshevsky is bound to lead to one of dismal nihilism. The protagonist of the novel undergoes a slow transformation into depravity as he embodies the beliefs upheld by the radicals of that day. This “Underground Man” understands that a world without God, is a world without law:

If you were to destroy in mankind the belief in immortality, not only love but every living force maintaining the life of the world would at once be dried up. Moreover, nothing then would be immoral, everything would be permissible, even cannibalism.

With Notes from the Underground, Dostoevsky had discovered a new genre of writing. His next works continued this investigation into the philosophical and psychological prevailing weltanschauung (worldview) of the day. Each of Dostoevsky’s characters in his subsequent novels embodies these beliefs. Through these characters, Dostoevsky shows his readers the logical consequences of abiding by those worldviews. A world that has broken the shackles of Christianity, and embraced the godless society of Chernyshevsky, would produce a living hell.

Over the next twenty years, Dostoevsky produced some of the greatest novels ever written. Within each, Dostoevsky heavily leans on his experiences as a young revolutionary as he warns the world and Russia of the path they are on. But his novels are much more than an investigation of the philosophies of that day — they are a prophecy of the revolution and death that is to come.

To be continued…

Photo by eluoec on Unsplash